I was doing some more research into the last comment by the Chairman to my post on how we could eliminate virtually all use of coal for electricity production. I was concerned that I had made a wild assumption that we could switch over to such a large proportion of gas use (up to 44% from 14%) in the short term. It turns out that we actually could (with a current known reserve of 849.5 billion cubic metres, and 43.6 billion cubic metres of production capacity, and currently predicted growth in that production capacity) provided we were willing to cut off about all of our exports.

However, the really interesting thing that came out of my analysis is what a completely achievable task reducing our carbon dioxide emissions to less than 50% of what they are now would be, and how apathetic and narcissistic we are as a species. See, what I did was make up a little spreadsheet to calculate the emissions of CO2 based on fuel mix to achieve our required amount of electricity production that I could then compare to the current and predicted availability of production rates for those fuels and still meet our Kyoto target value. I also used the following assumptions:

• No energy efficiency improvements

• Rise in electricity production required is 2.2% per year in line with GDP growth forecasting

• Data on emissions rates from various fuels from the US Department of Energy from July 2000.

Now just a comment on how amazingly conservative these assumptions lead me to be. First, there are credible estimates (Flannery, etc.) that about 80% of the reductions we would require to achieve the worldwide CO2 emissions reduction target could be done with bog-standard energy efficiency improvements alone using technology that has been around for decades. Second, I predicted a rise in electricity production required each year based on GDP, using the widely documented correlation between GDP growth and electricity usage (UN).

If anyone wants the spreadsheet to critique it, please let me know, but my findings are as follows.

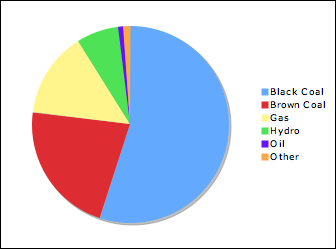

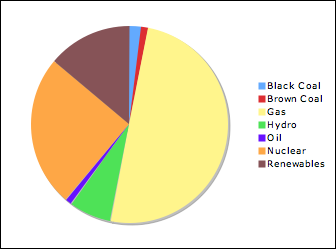

The base case I modelled is the current emissions with a breakdown of fuel from my 10 December post. The first really pathetic finding is that even currently burning coal to make up 77% of our electricity, Australia is still on track to meet its Kyoto commitments. The second thing I found is that with my 2020 case modelled, going to 25% nuclear and 44% gas to eliminate virtually all coal burning while achieving the 20% renewables target set by the government results in us passing our Kyoto target by a whopping 68%! Emissions using the above fuel mix would actually be only 45% of what they are today.

So, I then went back to see how far we could get by keeping some coal and dropping all the nuclear out of the mix to placate those that would rather burn coal than go nuclear. By doubling our gas usage (to 29%) and dropping coal back to 40%, we reduce emissions overall to half of the 1990 figure without any expansion of nuclear use.

The bottom line – this ain’t that tough, and the failure to actually commit to some solid changes that would be significantly less challenging than putting a man on the moon shows how much we have changed in 40 years, and not for the better.